January 22, 2020 | Nunavut

ARCTIC ORIGINS

Most busy thirty-something parents of two young children, looking for stability and a step back from hectic work lives, wouldn’t decide the answer lay in starting a wilderness lodge on the rugged shores of Baffin Island. But most parents aren’t Richard Weber and Josée Auclair.

By the mid-1990s, Richard had capped a string of polar firsts with the only ever unsupported out-and-back to the North Pole from land and the couple had pioneered commercial guiding in what is now Nunavut, building up a core clientele of adventurous Arctic devotees along the way. “But because they had these two little kids,” Tessum Weber says, referring to himself and his brother Nansen, “my parents said, well, we can’t be guides forever. We need to do something more sustainable. And my mom had the brilliant idea that, okay, we’ll start a lodge.”

The summer when Tessum was seven and Nansen five, while Richard was off guiding arctic sea kayak trips, Josée flew with the boys to the small settlement of Iqaluit at the northern end of Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island. Since being designated the capital of Nunavut in 1999, Iqaluit has experienced rapid growth in both population and visitor traffic, but, in 1997, the town was still small, sleepy. Josée tracked down an Inuit family who were among the last that still followed traditional nomadic practices and, choosing a characteristically straightforward approach, she knocked on their door and introduced herself. She explained she’d heard they traveled down the coast among outpost camps in summer, and she was wondering if she and her sons might come along. Traditionally, the Inuit hit each of their camps at the ideal time to hunt or fish there, and Josée understood that such a deep understanding of local wildlife was essential intelligence for someone choosing a spot for a lodge. The family elder, Inooki, then in his eighties, decided she looked hardy enough, and, as Tessum, now 30, puts it, “stuck us in this old fishing boat and away we go.”

The boat was light on the safety features (no railings) and creature comforts (the Weber contingent lived in the hold), but what mattered was the warmth with which Inooki’s family folded the newcomers into their lives and the generosity with which they shared their knowledge. Born far in the remote tundra, Inooki, who is still alive today at the age of 105, had walked alone to Iqaluit as a small child after his family was stricken with tuberculosis, following the birds. He lived through a troubled period when many Inuit were pressured or forced to move to permanent settlements, abandoning their ancestral hunting grounds and sustainable means of survival, but he was still eager to share his heritage. “I think he was happy there was this unusual family from the south that wanted to learn from him and appreciate what he grew up with, in the place that was his backyard,” Nansen says. “Even if we were still too little to do certain things ourselves, he’d explain like what you do with a caribou stomach or how you cut up a leg and carry it over your back.” Inooki might look at the sky and know that in two days it would snow. Or he might look at the tundra and predict with perfect accuracy when the caribou would come through. “I’ve never seen anyone able to do that,” Tessum says. “I think it’s a connection we’ve lost.”

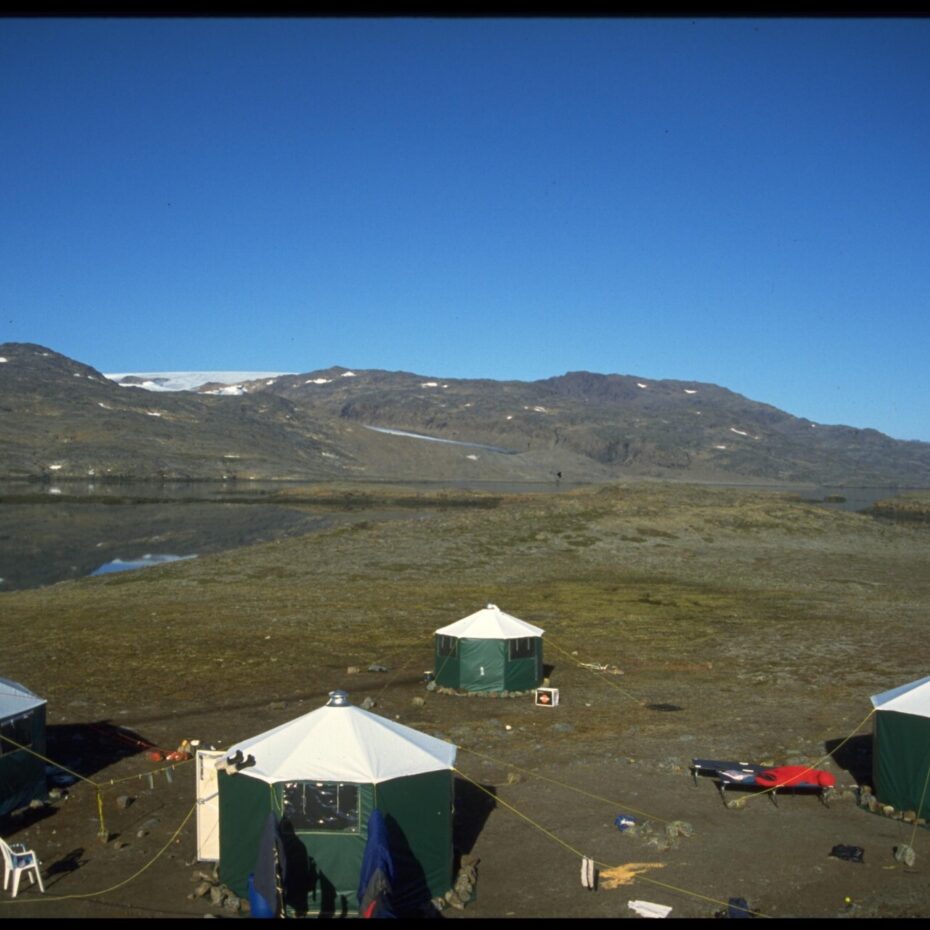

After three summers, Richard and Josée settled on a location on Jackman Sound, south of Iqaluit, and built a simple yurt camp with a kitchen house, shower house, and tents for half a dozen guests. During the day, while their parents were busy guiding glacier hikes or kayaking trips, Tessum and Nansen took full advantage of their status as free range (or, free tundra) children and made use of the skills they’d learned from Inooki’s family. “If you’re hungry, well, there’s a lake five kilometers away. Go get some fish,” Nansen says. “Or we’d see a gyrfalcon up on a cliff, and Tessum and I would go scrambling up to try to have a look at the chicks. We knew not to do certain things, like not to go on the glacier because of crevasses, but pretty much as long as we could see camp, it was a free for all zone.”

“Our job was to help out around camp and then go off and play and explore,” Tessum says. “As long as we had a shotgun and had the dogs with us, my parents would cut us loose.” For Webers of all ages, dangers isn’t to be avoided but to be assessed and mitigated, met with a cool head. And, of course, discretion is sometimes the better part of valor, like the time when Tessum and Nansen became aware they were being stalked by two wolves while fishing for Arctic char. “We told the dog to chase off the wolves and went running back to mom and dad,” Nansen says. Another time, in the midst of an early season snowball fight, Tessum startled a polar bear out of a snow patch. Fortunately, both ran in opposite directions.

“Looking back,” says Tessum, “I think it was one of our most formative years. When you’re young and you get put in these very extreme situations, you learn to become quite self-reliant and deal with issues as they come. You want to survive and thrive, so you get out there and get going.”

“If you’re a little kid running around, yeah, you’re going to get stuck in the mud,” Nansen adds, “and you’re going to fall and hurt yourself, but you learn from it. And being so remote, you have to be smart, even if you’re only six years old.”

One summer at Jackman Sound was enough to make clear that the location was not right for a lodge. “It was too adventurous,” Tessum says. “The logistics of getting there and the level of intensity simply didn’t work.” The Webers wanted a spot where guests would have a good chance of seeing polar bears, but the yurt camp was overrun with them. Four bears teamed up to trash the camp. One visited every day for more than two weeks. Josée, stalked by another while walking back from the shower house, scared it off by growling at it, a technique not all guests would be capable of mimicking. When the bears weren’t wreaking havoc, the weather was, like when 110 km/hr winds blew down the tents in the middle of the night, necessitating a 2:00am all-hands-on-deck scramble to collect scattered gear and gather rocks for ballast.

The Webers, accustomed to shaping and refining their approaches to harsh environments through trial and error, weren’t deterred by the failed experiment at Jackman Sound. When, soon after, they heard about a bankrupt beluga whale watching lodge for sale on Somerset Island, they sensed the potential for a location with the right balance between adventure and accessibility. The main lodge structure of what would become Arctic Watch had been standing empty for a long time when the family first saw it and was essentially an empty, musty, moldy shell. “My parents had the vision for what it could be,” Tessum says, “and we had the backing of a loyal group of guests who believed in us.”

At the end of every season at Arctic Watch, Tessum and Nansen, still kids, were let loose on Somerset with ATVs and camping gear for a few days to pursue their own adventure agenda and help uncover everything the new local territory might offer guests. It’s something of a paradox how the independent natures of the four Webers have fused into tight bonds of trust and respect among the family members, but without the freedom they were given, Tessum and Nansen wouldn’t have had the opportunity to prove their value to the family business and earn their status as collaborators. When time came to expand into a second lodge, Arctic Haven, Nansen, then only twenty but with a long-established talent for finding wildlife, was delegated to spend two months scouting the environs. Now Tessum and Nansen’s mutual passion for exploring new places and pushing boundaries has led to their spearheading the family’s new Baffin Island heli-skiing operation. “Setting that up meant going back to square one,” Nansen says, “but it’s super exciting to have a whole new territory where no one’s doing what you’re doing and no one’s going to help you.”

Patience, openness, humility, and a bit of daring are key ingredients in brewing meaningful wilderness expertise, and it’s the purposeful accrual of experience that has carried the Webers from the hold of an old Inuit fishing boat to Somerset Island and Ennadai Lake and now back to Baffin again, this time in a helicopter.

“If it’s never been done before,” Tessum says, “you might fail spectacularly, or it might be really amazing. If you don’t try, you’ll never know.”

We're here to help.

We understand that booking a trip like this is a big endeavour. Please reach out to us with any questions that you might have regarding your upcoming adventure.