GETTING THE SHOT WITH NANSEN WEBER

Featured

Featured

June 25, 2020 | THE CANADIAN ARCTIC

Where would we be without wildlife photography? A century ago, illustrations in books were the best encounters with distant and rare species most people could hope for without being actual explorers or scientists. Now the world is saturated in an astonishing array of images of animals living in every possible environment.

Those who will never visit the Serengeti can still accurately imagine giraffes and elephants roaming among its acacia trees because they have seen hundreds of such scenes. Very few of us will ever visit an emperor penguin colony during the brutally cold Antarctic spring, but we can picture the adults bending over their fluffy grey chicks. Someone who’s never left their hometown might easily know what humpback whales look like underwater, how a certain Indonesian insect appears in extreme close-up, and how a salmon might leap into the waiting jaws of an Alaskan brown bear. We can know these things without enduring long journeys or extreme cold or heat or spending months waiting silently in a jungle blind.

But, of course, nothing compares to getting out there for ourselves. For many, a desire to make images brings them into wild environments. For Nansen Weber, lead photographer for Weber Arctic, it was the wild environments that brought him to making images. As a fourteen-year-old with a knack for wildlife and who was accustomed to getting around Somerset Island on his own, he was assigned to guide Arctic Watch guest (and eventual fixture) Gretchen Freund in search of wildlife to photograph. “For the first two weeks, I was just kind of sitting around,” he says, “but finally she told me to go get the second camera and make myself useful.” Over that summer, she taught him the basics, and even though he didn’t take photos the rest of the year, they picked up shooting again the following summer, a seasonal tradition that would last for a decade.

During that period, Nansen’s photography education got a major boost when the crew of the BBC’s Frozen Planet came to film their beluga segment in Cunningham Inlet and, now seventeen, he again served as guide. “What I learned from the BBC guys or NatGeo is being really selective,” Nansen says. “It’s not just about just getting a decent image. It’s one in ten thousand. If a polar bear is walking on the ice, there are thousands of images of that. How are you going to make it different?” As far as his goals for his own images, Nansen prefers close-up shots that convey something about the animal’s animating intelligence and consciousness. “I look for the intensity in the animal’s face and the expression in his eyes, when you feel he’s looking at you and you’re both thinking.”

Rather than studying photography in a formal setting, Nansen continued learning in the field and picking up tips from the occasional YouTube video. His longest lens is a 200mm with extender, relatively small for wildlife work, but he partly credits the limitations of his gear with teaching him to be more patient and to learn how to (respectfully, safely) sneak up on his subjects. At twenty, he got another foot in the door via a National Geographic Young Explorers’ grant for beluga ID work, and, just after he’d started university, he landed his first assistant job when acclaimed underwater and marine wildlife photographer Brian Skerry needed last minute help on a story about bluefin tuna in Nova Scotia. “I think it was like, can you be there tomorrow?” Nansen says. “And, yeah, of course I went.” His lifelong experience in the Arctic made him an especially valuable team member, an outdoor fixer knowledgeable not only about wildlife but about the practicalities of weather and light and setting up camp. “Spending a month or two out in the middle of nowhere finding things and tracking things is where my expertise is,” he said. “This is my backyard.”

When drones came on the scene, Nansen embraced their capabilities for capturing dramatic Arctic vistas and for photographing wildlife without intruding or disrupting their behavior. In his parents’ basement, he build a camera trap, a remotely activated camera triggered by motion that allowed him to leave a camera in the wild for extended periods in hopes of capturing animals going about their business. For two years, he tried to get a shot of an elusive wolverine near Arctic Haven, first by enduring a frigid stakeout in a blind and then with his camera trap. “They’re smart,” Nansen says, “so he’d always put his back to it. Or I’d get a foot or a piece of his tail. Or a bunch of seagulls would hang out in front of it and drain the battery.” After what he estimates as 30,000 to 40,000 shots, the wolverine happened to turn and look at the camera trap right at golden hour, bringing Nansen’s quest to a successful conclusion. The trap itself later met a bad end, however, when it was buried in an avalanche in British Columbia.

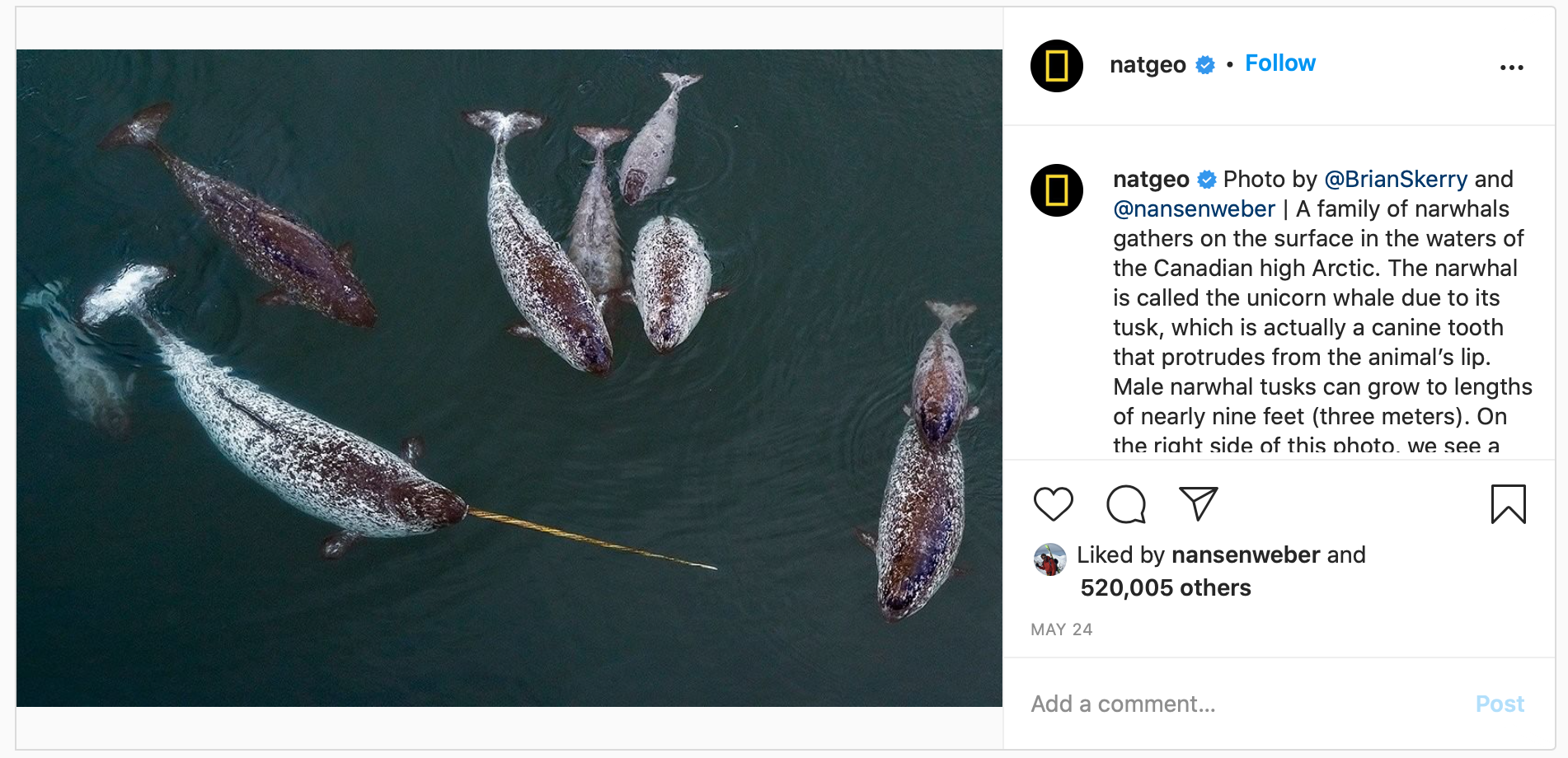

If you’re one of National Geographic’s 138 million Instagram followers, in late May you might have noticed an arresting aerial shot of a group of narwhals in dark jade water, including a speckled calf riding on its mother’s back. The image is the product of a collaborative effort by Nansen and Brian Skerry and is part of an upcoming story for the magazine. Nansen and Skerry started by spending three weeks photographing belugas at Arctic Watch, during which time they observed calves with fetal folds and umbilical cords—new evidence that the animals give birth in Cunningham Inlet rather than calving elsewhere before they arrive. “I’ve been at Arctic Watch twenty years,” Nansen says, “and every summer there’s something new.” Conditions proved unexpectedly challenging for photographing the belugas, with lots of ice and few clear days. Even more frustrating was the intrusion of Zodiacs from a passing research vessel that scared away hundreds of belugas during a rare moment of good weather.

Nansen had known that photographing narwhals would be much more difficult, and indeed it was. The location south of Arctic Watch where the whales hang out was icy and foggy, and the photographers spent two weeks in a leaky plywood cabin waiting for their chance. “It was brutal,” Nansen says, “but you couldn’t do anything because of the fog. You could hear the whales playing and blowing off shore, and you could hear walrus making their crazy sea monster sounds, but it’s so risky getting in the water with pack ice. If the motor stops, you’ll be out in the middle of nowhere in the fog.” Finally the fog lifted. They got the boat in the water and moved as quietly as possible toward the narwhals. They shot with the drone, and then Skerry got in the water for an hour in hopes of photographing the whales underwater. Nansen had the tense job of monitoring the ice from the boat, as well as keeping an eye out for walrus and bears. Ultimately, their most extraordinary shots came from the drone, as the water was murky. But photographers understand patience as an essential virtue and live by their hopes for next time.

When Nansen guides Weber guests who wish to photograph wildlife, one of his core pieces of advice is not to get too tied up in a checklist of shots. “It’s best just to go out and see what nature has to offer. I saw that with the BBC guys, too. Their whole careers are based on getting one or two specific images, but they still keep an open mind.” Nature is always in charge, always unpredictable, and the unplanned image might end up being the most truthful. “Let’s just get out there and see what’s going on,” Nansen says. “That’s the best expectation.”

We understand that booking a trip like this is a big endeavour. Please reach out to us with any questions that you might have regarding your upcoming adventure.