UNICORNS OF THE SEA: NARWHAL

Featured

Featured

February 19, 2020 | Arctic Watch

Narwhal are a toothed whale that have captured the imaginations of travellers for centuries. A bizarre ivory spear (actually a tooth) that extends from the whale's face distinguishes this whale from other species seen in the Canadian Arctic.

Like the beluga, narwhals are medium sized whales. Ranging in size up to 10 feet, the males are generally larger than females. At around 13 years old, males become sexually mature; females at about 5 to 8 years old. Minimal information on population numbers in Canada exisist. It is estimated that there is approximately 50,000 individuals in the Arctic. Narwhal are famed for their ivory tusk - a helical tusk which is an elongated upper left canine (typical to males). These tusks were traditionally used by nomadic Arctic peoples to fashion tools such as spear heads, fish hooks, arrow heads and more.

Little is known about the use of such a large tusk - narwhal are known to have tusks as long as 10.5 feet. It is thought the tusk is used for “sensing” routes in the spring ice as they migrate in the Arctic, for mating rituals and more recently, narwhal have been observed “slapping” or hunting fish (polar cod) with their tusks. In 2017, the department of fisheries and oceans captured footage of narwhal “slapping” fish:

Narwhal are thought to live up to 50-years. A source of food for orcas and polar bears, a narwhal’s skin (called “muk-tuk”) is extremely rich in vitamin-c and iron; it was consumed by early Inuit as a way to fend off scurvy. Narwhal are closely related to beluga whales and have been known, on rare occasions, to interbreed (” see narluga”).

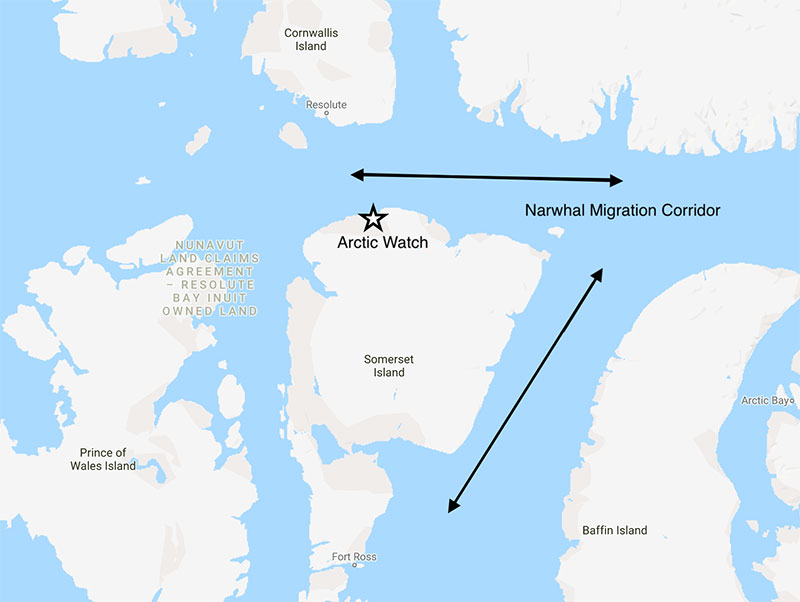

Narwhal tend to congregate in smaller numbers than beluga whales (for example, at Arctic Watch, we’ve witnessed congregations of belugas pushing 2000 animals). Their summer groups typically contain five to ten individuals as they migrate between winter and summer feeding areas. These whales exhibit seasonal migrations that typically return to the same locations year-over-year. Their diets are highly specialized; typically consisting of Arctic char, cod, Greenland halibut squid, capelin and shrimp.

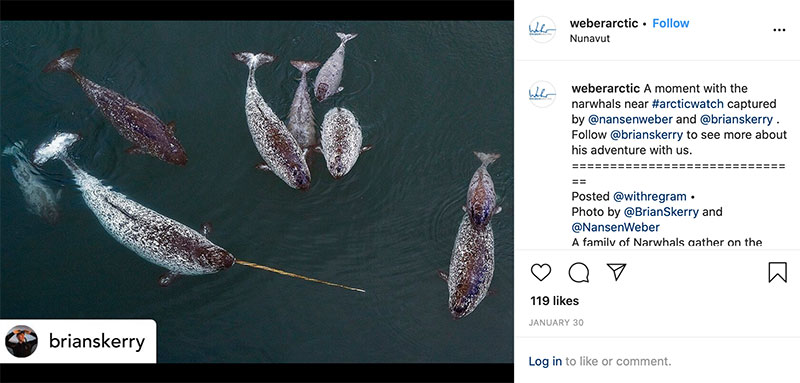

Photographers Nansen Weber and Brian Skerry recently captured several stunning images near Arctic Watch, as part of an upcoming story in the National Geographic Magazine. While most of the images are under wraps until the story is published, we’re very happy to share this one gorgeous photo, captured in the evening Arctic light:

On Somerset Island, we generally see these whales migrate past Arctic Watch in August. There are several autumn feeding areas where the whales will return yearly to feed on cod and Arctic char. As these whales have a higher frequency of staying in small groups, we typically observe them in the deeper waters of the Northwest Passage. A twin otter is a great way to observe these gorgeous mammals unobtrusively - flying quietly above as they migrate through the Arctic waters of the Northwest Passage. Guests will often ask when is the best time to see Narwhal - we recommend our Ultimate Arctic Experience in August.

We understand that booking a trip like this is a big endeavour. Please reach out to us with any questions that you might have regarding your upcoming adventure.